Benefits

How Wilderness Benefits You

The heart of the Wilderness Act is recognition of the value of wilderness, yet this value goes well beyond activities like camping and hunting. The actual language in the Act devoted to that subject is very concise—it's a document of action, after all, mostly concerned with the logistics of implementation and rules yet peppered with eloquent language defining the essence of wilderness.

The Act suggests wilderness is valuable for its "ecological, geological, or other features of scientific, educational, scenic, or historical/cultural value." Wilderness is often said to represent a "baseline": a landscape with a mosaic of ecosystems that function with as little influence from human beings as any on Earth. To explain the nuances of our influence in other, more manipulated or modified sites, it's useful to reference wilderness processes.

The Wilderness Act also defines wilderness as a place with "outstanding opportunities for solitude or a primitive and unconfined type of recreation," and one purpose of protecting such places as "for the use and enjoyment of the American people in such a manner as will leave them for future use and enjoyment as wilderness."

How do we boil down these wide-ranging values into categories to better understand them-a process that has much bearing on how we protect and manage wilderness areas? Some of them fall easily into one or another; some transcend boundaries. Some are even difficult to explicitly define.

Direct Vs. Indirect Values

Humans ascribe values to wilderness as a specific place, an experience, a symbol, and/or a resource. An economic analysis of wilderness may consider its direct and indirect values as a commodity. Indeed, all wilderness values can be assessed that way, although not all will fall exclusively into one or the other category. Direct values are those gained from firsthand contact with wilderness; many of these may also be called "experiential" values. Recreation—backpacking, rafting, or hunting—is one example. Another is education, as when one learns about biology, ecology, or geology directly through observation of and interaction with wilderness features and systems.

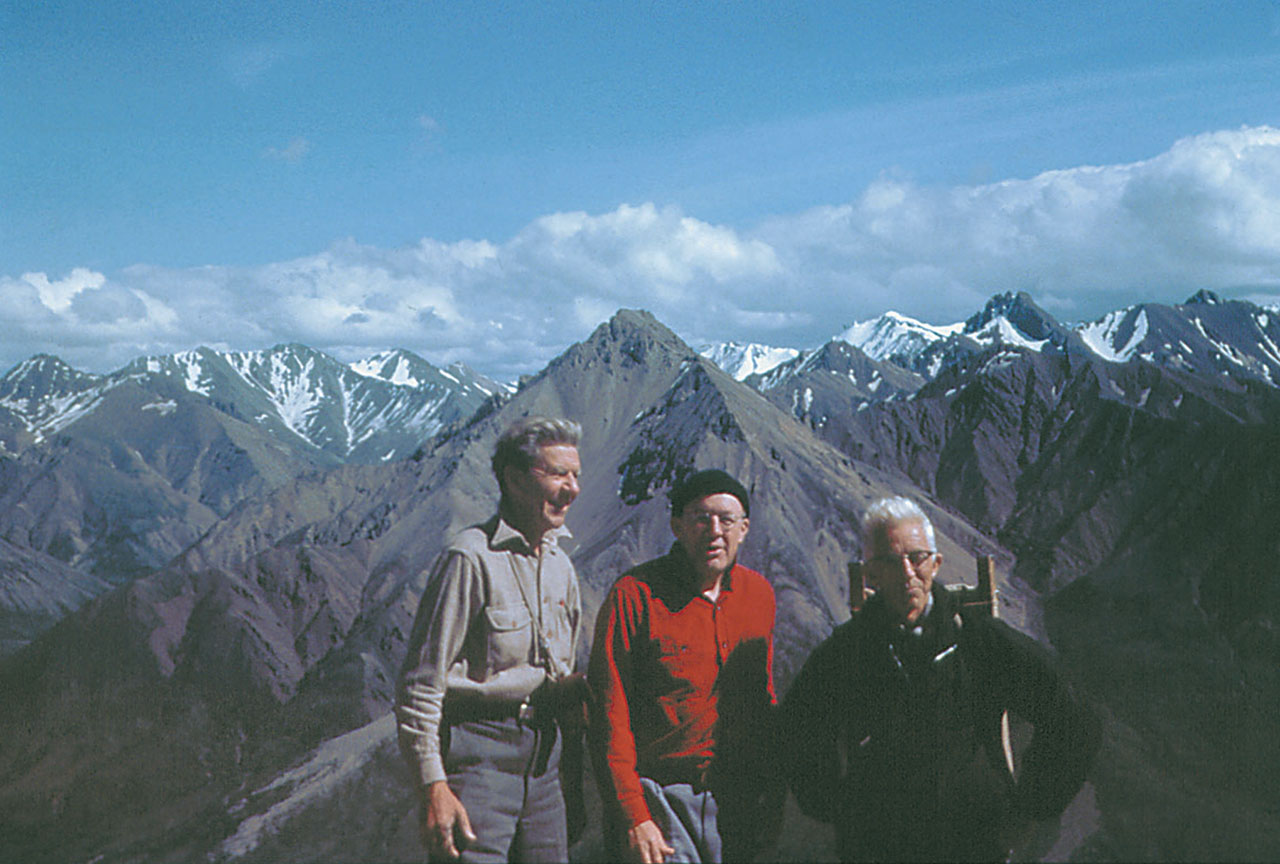

Experiential wilderness qualities cover a wide gamut of potential benefits. One person might be seeking the challenge of navigating and traveling in a wilderness setting—either as a test of physical and cognitive skills, or to enact what's perceived as a formative human experience. Another, however, may have no more goal than to spend time in the wilderness, with whatever may come in terms of adventure, scenery, and other experiences.

Indirect values are those not contingent on (though often related to) direct experience of wilderness. The knowledge that wilderness will be around for your descendants to enjoy is "bequest value," while "option value" (sometimes classed as its own category alongside direct and indirect values) describes the opportunity for you to both directly and indirectly benefit from wilderness in the future. The intrinsic value of wilderness is that beyond any human evaluation or connection: wilderness for wilderness's sake.

There's no place on Earth entirely free of human impact, but in wilderness areas, anthropogenic activities aren't the dominating forces. The characteristics of diverse, dynamic wilderness ecosystems are esteemed by humanity across a broad spectrum. Some class the typically high air and water quality of wilderness areas as social services, while others especially value wild places as habitat for plants and animals scarce or absent in more human-modified geographies. Wilderness' ecological integrity—its biological and genetic diversity, the caliber of its natural resources—ranks high among the qualities of greatest interest to Americans, whether as the subject of scientific inquiry or as a fundamental intrinsic value of wilderness celebrated by society.

Across cultures and history, people have also attached symbolic values to wilderness. This symbolism can take a spiritual tack, as in the writings of John Muir, who viewed wilderness as everywhere imbued with divine beauty. Some may see wild places as emblematic of other values they cherish, such as freedom and opportunity, or of nature in general. The idea that wilderness represents something nourishing and fortifying for the human spirit—even for those who never tread in one, and beyond any practical and scientific benefits—has been cited by many of its most famous proponents. "In wildness is the preservation of the world," Henry David Thoreau famously wrote in his essay, "Walking." In A Sand County Almanac, conservationist/ecologist Aldo Leopold asked, "Of what avail are forty freedoms without a blank spot on the map?"

All people don't share the same perceived benefits when it comes to wilderness, and an individual's values can shift over time. One's impression of wilderness worth seems to stem in part from direct experience with wilderness as well as the influence of other people. For many individuals, "wilderness" means a very specific place, one with which they've developed a highly personal and meaningful relationship over decades. Research suggests such familiarity alone—built from a fundamental association of a particular riverbank, mountaintop, or grove with memories and traditions—can rank near or at the top of a person's wilderness values.

In sum, wilderness benefits are many and varied. In light of the "direct vs. indirect" distinction, it's important to remember that those who value wilderness may include not only a devoted trekker who spends weeks of the year in the backcountry, but also a city-dweller who never visits a federal wilderness area in his lifetime.

Public Opinions about Wilderness Values

Public opinion surveys have helped to define these benefits and values. Overall, when compared to previous decades, more people consider the various direct and indirect benefits of wilderness to be increasingly important. In fact, recent data from the National Survey on Recreation and the Environment indicate that protecting air quality, water quality, wildlife habitat, unique wild plant and animal species, and bequest to future generations are all consistently rated as the top five most important benefits of wilderness.

Most Americans, whether urban or rural, also ascribed high importance to six additional benefits including the scenic beauty of wild landscapes, the knowledge that wilderness is being protected (existence value), the choice to visit wilderness at some future time (option value), the opportunity for wilderness recreation experiences, preserving nature for scientific study, and spiritual inspiration.