Howard Zahniser

Howard Zahniser was born on February 25, 1906, in Franklin, Pennsylvania. The son of a Free Methodist minister who changed churches every few years, he grew up in the Allegheny River region of northwestern Pennsylvania. He spent his teenage years in Tionesta, just west of what is now the Allegheny National Forest. It was here that he developed a life-long interest in nature and a love of literature. He attended Greenville College in Illinois where he received a degree in humanities. He taught school and worked as a newspaper reporter.

Zahniser wrote the first draft of the Wilderness Act in 1956. He chose the word "untrammeled", suggested by Pauline "Polly" Dyer, to characterize wilderness in the Act. Others questioned this choice, yet he was adamant about its use as the right word to characterize wilderness, as Polly had done to describe the imperiled beaches of Olympic National Park in the late 1950s.

Zahniser wrote the first draft of the Wilderness Act in 1956. He chose the word "untrammeled", suggested by Pauline "Polly" Dyer, to characterize wilderness in the Act. Others questioned this choice, yet he was adamant about its use as the right word to characterize wilderness, as Polly had done to describe the imperiled beaches of Olympic National Park in the late 1950s.

"A wilderness...is hereby recognized as an area where the earth and its community of life are untrammeled by man..." - The Wilderness Act.

Beginning in 1930, Zahniser was employed by the U.S. Department of Commerce and soon the USDA Bureau of Biological Survey (which would several years later become the core agency of the new USDI Fish & Wildlife Service). He worked for 12 years for the Fish & Wildlife Service in the information division where he honed his interests in nature, influenced by the likes of Ira Gabrielson and Edward Preble, as well as doing his own research, writing, and editing. He worked at writing press releases, speeches for agency directors, radio scripts for the National Farm and Home Hour (in which he sometimes appeared himself). In 1942, after the start of World War II, the Fish & Wildlife Service was relocated to Chicago, but Zahniser found work in the USDA Bureau of Plant Industry, Soils, and Agricultural Engineering. He worked as the director of the Bureau's information and editorial division.

During this time as a federal employee, he contributed articles and essays to scholarly and scientific journals relating to the conservation/environmental movement. Zahniser's ideas about ecosystems and wilderness were influenced heavily by Harold Anderson, Harvey Broome, Bernard Frank, Aldo Leopold, Benton MacKaye, Bob Marshall, Ernest Oberholtzer, Olaus Johan Murie and Robert Sterling Yard, who were driving forces behind the fledgling wilderness movement and the formation of The Wilderness Society (founded in 1936). In 1945, Murie became director of The Wilderness Society in Moose, Wyoming, and at approximately the same time, Zahniser left the federal government and became the executive secretary of the organization in Washington, D.C. Murie and Zahniser led the organization and built a broad basis for support. Both were pivotal in the passage of the Wilderness Act of 1964.

In the late 1950's, Howard Zahniser convinced a Georgetown tailor to custom-make a coat with four supersized inside pockets in which he would keep books, wilderness bill propaganda, Wilderness Society membership information and applications and other items.

In the late 1950's, Howard Zahniser convinced a Georgetown tailor to custom-make a coat with four supersized inside pockets in which he would keep books, wilderness bill propaganda, Wilderness Society membership information and applications and other items.

I believe that at least in the present phase of our civilization we have a profound, a fundamental need for areas of wilderness - a need that is not only recreational and spiritual but also educational and scientific, and withal essential to a true understanding of ourselves, our culture, our own natures, and our place in all nature.

This need is for areas of the earth within which we stand without our mechanisms that make us immediate masters over our environment - areas of wild nature in which we sense ourselves to be, what in fact I believe we are, dependent members of an interdependent community of living creatures that together derive their existence from the Sun.

By very definition this wilderness is a need. The idea of wilderness as an area without man's influence is man's own concept. Its values are human values. Its preservation is a purpose that arises out of man's own sense of his fundamental needs.

- Howard Zahniser, The Need for Wilderness AreasIn the 1910s and 1920s, there were several proponents of wilderness. Three men are considered pivotal in these early years and all were Forest Service employees: Aldo Leopold, Arthur Carhart, and Bob Marshall. Their efforts were successful at the local level in creating administratively designated wilderness protection for several areas across the country beginning in 1924 with the designation of the Gila Wilderness on the Gila National Forest. At the national level, there was a series of policy decisions (L 20 and U Regulations) that made wilderness and primitive area designation relatively easy, but what was lacking was a common standard of management across the country for these areas. Also, since these wilderness and primitive areas were administratively designated, the next chief or regional forester could "undesignate" any of the areas with the stroke of a pen. This situation was considered to be unacceptable by Zahniser and others.

Zahniser became the primary leader in a movement to have Congress designate wilderness areas, rather than the federal agencies. In the late 1940s and early 1950s, he led conservationists of the era to successfully fight the Echo Park Dam. This was a Bureau of Reclamation proposal in 1949, to build a substantial hydroelectric project in Dinosaur National Monument as part of the Upper Colorado River Storage Project. The dam fight came to symbolize the nation's endangered parks and wildernesses. Zahniser served as a representative of conservation interests in negotiations with the government, and the issue was finally resolved in 1955 with no dam being built. With the support he had garnered from the conservation community during the dam fight, he went on to be an important leader in the campaign for federal wilderness legislation in the 1950s and early 1960s.

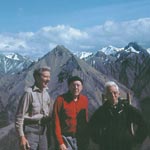

Olaus Murie, Howard Zahniser and Adolph Murie (left to right) on Cathedral Mountain in what is now Denali National Park.

Olaus Murie, Howard Zahniser and Adolph Murie (left to right) on Cathedral Mountain in what is now Denali National Park.

"Let's try to be done with a wilderness preservation program made up of a sequence of overlapping emergencies, threats and defense campaigns! Let's make a conserted effort for a positive program that will establish an enduring system of areas where we can be at peace and not forever feel that the wilderness is a battleground."

- Howard Zahniser, "How Much Can We Afford to Lose?," in Wildlands in Our Civilization (San Francisco: Sierra Club, 1964): 51.

This address was also printed in the Sierra Club Bulletin (April 1951).

In 1946, proposed legislation for a Federal Wildlands Project articulating the vision of Benton MacKaye, then president of The Wilderness Society, was circulated, though it was never introduced into Congress. The lack of support for this proposed legislation showed Zahniser that substantial national support would be needed to achieve wilderness legislation. By 1949, Zahniser had a detailed idea for federal wilderness legislation in which Congress would establish a national wilderness system, prohibit incompatible uses, identify appropriate areas, list potential new areas, and authorize a commission to recommend changes to the program. It was not until after the Legislative Reference Bureau report on wilderness was published legitimizing concern for wilderness and the Echo Park Dam fight united the conservation community, however, that the first wilderness bill would be drafted.

In 1955, Zahniser began an effort to convince skeptics and Congress to support a bill to establish a national wilderness preservation system. Drafts of a bill were circulated the next year and introduced in Congress by Rep. John P. Saylor (R-PA). He sought to rally public opinion through writing in The Living Wilderness and other publications as well as organizing many talks to citizens groups across the country. By the late 1950s it seemed that the wilderness bill would eventually become law, but there were many legislative battles still to be fought. At the same time, the Multiple Use, Sustained Yield Act (MUSY) was also being pushed through Congress. Some have said that the MUSY was strongly supported by the Forest Service to counteract the wilderness legislation, and after passage of MUSY in 1960 there were many who felt that there was no need for a separate wilderness bill since wilderness was one of the many multiple uses allowed in the act.

Hubert H. Humphrey (D-MN) became a major supporter of the bill, but state water agencies, mining, timber, and agricultural interests were very much opposed. Also, the Forest Service and the National Park Service both initially opposed the bill not wanting to give up administrative control. The wilderness bill, which was stalled for several years in Congress, finally came out of committee with a compromise to allow mining in national forest wildernesses until 1984.

Howard Zahniser's son Ed recalled, at a national wilderness conference in 2000, that on Saturdays, it was his father's job to take the four children out of the house for "Zahnie's Rational Spousal Preservation System," and take them for hikes along the C&O Canal or to the National Mall museums and art galleries. He recounted that some of the Saturdays were devoted to Capital Hill visits where the four children could be found distributing Wilderness Act pamphlets to remaining members of Congress. Ed said, "We four kids could talk wilderness first hand...Did our squeaky-voiced squadron of Saturday lobbyists turn a heart or two? Who knows?" Ed, a conservationist in his own right, shares other insights about his father in "Preserving Wilderness and Wildness as Enlarging the Boundaries of the Community."

Ironically, Howard Zahniser who pushed so hard for the act died on May 5, 1964, just a few months before the bill became the law of the land. Doug Scott, policy director of Campaign for America's Wilderness recalled Howard's last days. "Zahnie [as he was affectionately known] wasn't there to see it [the wilderness bill]...Just two days after testifying at [the final congressional hearing], Zahnie died at the age of 58...But, his widow, Alice, and the incomparable Mardy Murie stood at Lyndon Johnson's side when the wilderness law was passed." President Lyndon Johnson signed the bill into law on September 3, 1964. The act designed 9.1 million acres of wilderness in the new National Wilderness Preservation System, most of these coming from the national forests. Because of Zahniser's relentless efforts, he has often been called the "Father of the Wilderness Act."

A team of Forest Service wilderness managers met soon afterward in Washington D.C. to come up with implementing regulations for these new congressionally established wildernesses. What was felt to be an easy task eventually took many months as they sought consistent ways to manage the existing wildernesses. Part of the Wilderness Act of 1964 also set up procedures to evaluate existing primitive and roadless areas for possible inclusion into the wilderness system. For the next 20 years the roadless areas reviews (RARE and RARE II) would play an important and controversial role in Forest Service management of the national forests.

From September 1945 to May 1964, Zahniser served as executive secretary of The Wilderness Society, editor of its journal The Living Wilderness, and later executive director. In addition to Zahniser's role in The Wilderness Society-and the passage of the Wilderness Act of 1964--he played important roles in other conservation and environmental groups from the mid-1940s until his death. He wrote extensively for the Nature Magazine, where he contributed a monthly book review column from 1935 until 1960; organized the Natural Resources Council of America in 1946 (he served as the chairman 1948-49); served on the Secretary of the Interior's Advisory Committee on Conservation from 1951 to 1954; and was honorary vice-president of the Sierra Club after 1952, vice-chairman of the Citizen's Committee for Natural Resources in 1955, and president of the Thoreau Society for the 1956-1957 term. He was awarded the honorary Doctor of Letters (Litt. D) degree by Greenville College in 1957.

Preserving Wilderness and Wildness as Enlarging the Boundaries of the Community

By Ed Zahniser, son of Howard Zahniser

Howard Zahniser, or 'Zahnie' as he was known to friends and associates, grew up largely off the money economy and so did not get eye glasses until well into his youth. With their aid he discovered that the world had sharper edges and even greater natural beauty than he had previously imagined. A public school teacher introduced him to birdwatching and inspired a lifelong fascination that no doubt attracted him to his eventual work in conservation.

Another public school teacher required her pupils to memorize a quotation from Ralph Waldo Emerson each week. She would point at you, my father said, and say "Emerson says!" You were supposed to snap back with the Concord Transcendentalist sage's quote for that week. Birds and Transcendentalism: with the metaphysical humility of his religious upbringing these (and later mentors) sufficed to point Zahnie toward concern for preserving wildness.

Zahnie's important mentors after he went to Washington, D.C. in the 1930s were the naturalist Edward A. Preble, mammalogist Olaus J. Murie, and nature editor Richard Westwood. It was for Westwood, no doubt with support from Preble, that Zahnie wrote his monthly book review column, in essay format, "Nature In Print," in Nature Magazine for 25 years. These 12-yearly essays kept Zahnie abreast of contemporary nature writing and allowed him to dip into the rich legacy of past writing about natural values. This reservoir of knowledge served him well not just as a writer but as a lobbyist and champion of wilderness and wildness.

Not a little of Zahnie's writing in the wilderness bill years from 1955 to his death in 1964 was composed in his head as he would sit in our living room in front of the amplifier listening to recorded classical music after dinner. Perhaps he was also soaking in another ambience of that room; against one wall was a large, five-unit glass-front bookcase that held his 2,000 books of poetry and drama. He was a bibliophile, which is Greek for 'book junkie.'

As a young kid I got free books from two secondhand book dealers in Washington, D.C. They thus secured my innocent complicity so my father could browse undisturbed. When I was in high school, we regularly went to the Riverdale Bookshop, a secondhand bookstore within walking distance of our home in Hyattsville, Md., on Wednesday evenings. "Are you ready to go to prayer meeting?" my father would ask after our Wednesday dinner.

The outer walls of our first- and second-floor hallways were lined with floor-to-ceiling bookcases, whose contents doubled as insulation, lacking in the walls themselves. Zahnie's book collecting centered on three main areas: natural history and conservation, art, and literature. My father's main literary mentors were the Hebrew scriptures' Book of Job, Italian poet Dante Alighieri, English engraver and poet William Blake, and Henry Thoreau. These were Zahnie's mentors not only as a writer but as a humanist conservation thinker, too.

Around the time the wilderness bill was introduced, my father found an older tailor, E. 'Sye' Silas, in Georgetown who custom-made suits for about the same price as off-the-rack suits. My father convinced Mr. Silas to make him suits whose coats featured four supersized inside pockets. These became veritable fabric filing cabinets that usually held wilderness bill propaganda, Wilderness Society membership information and applications, a book by Thoreau, and another book by either Dante or Blake. Most conservationists and their organizations were poor then, so my father read these while riding trolley cars and buses, not taxi cabs, to appointments around the Nation's Capital. Some of his books still hold transit transfer coupon bookmarks.

The Wilderness Act is often cited as an unusually poetic piece of legislation. An article in the April 6, 2004 U.S. News and World Report magazine for example, says its language "tiptoes as close to poetry as legalese ever comes." Zahnie's lifelong immersion in the Job material, Dante, Blake, and Thoreau inform both the language and spirt of the Act. These are thinkers who held overweening Reason and unquestioned Progress suspect and who imagined their worlds anew.

Zahnie delighted in word play, one of his most oft-used tools of humor. During the wilderness bill years my sister Karen's Teddy bear became variously known as 'Wilderness Bill' or 'Gladly the Cross-eyed Bear.' The first moniker is self-evident. The second nickname parodies the evangelical Christian gospel song 'Gladly the Cross I'd Bear.'

When Zahnie began to edit and produce The Living Wilderness magazine in 1944, his very broad, humanist conception of conservation soon manifested in the "News Items of Special Interest" section he introduced in the March 1946 issue. Through this extensive section Zahnie and The Wilderness Society began to reach out to any and all groups and causes sympathetic to a broadly construed conservation ethic. The many bridges to other groups first built through the magazine's news section eventually helped fashion the first national conservation coalition, which would defeat the Echo Park dam proposal in 1955 and then launch the campaign for a Wilderness Act.

In these "News Items" appear Thoreau Society efforts to save Walden Pond from untoward development and the varied conservation concerns of national and state Women's Clubs and Garden Clubs. These latter two women's groups would supply a great deal of the political muscle and letter writing support that defeated the powerfully backed Echo Park dam proposal and that won the campaign for the 1964 Wilderness Act. Zahnie served as president of the Thoreau Society for the 1956-57 term. I find it characteristic of the inclusive humanism that underlay his conservation ethic that he invited as guest speaker for the 1956 annual meeting of the Thoreau Society not a conservationist, per se, but an Indian diplomat. Mr. Mehta, as I recall his name, was asked to talk about Thoreau's influence on Mahatma Mohandas Gandhi and the nonviolent resistance that freed India from British rule.

My feeling is that the bedrock of my father's commitment to a broadly construed conservation, and his assertion that the natural world, its wildness and wilderness, must be valued for itself as well as for humans, lay in his grasp of metaphysical humility. This need for sensing dependence and interdependence as well as independence is most clearly expressed in Zahnie's 1955 essay "The Need for Wilderness Areas." He asserts there that we prosper only as the whole community of life on Earth that derives its sustenance from the Sun prospers. Zahnie came by this urgent sense of our need for humility as a species genetically, from his parents and their religious commitment.

Although he did not end up espousing all the doctrinal views they stood for, Zahnie's view of life was essentially religious. When I was in junior high and high school, he and I sometimes would go to the National Episcopal Cathedral in Washington, D.C. on Sunday mornings. There we might attend two or three services; the cathedral's several chapels accommodated ethnic Christian groups, on a given Sunday. His religious sense was as broadly ecumenical for its day as the News section of The Living Wilderness was broadly conservationist for its time.

In a sense, with the Wilderness Act Howard Zahniser forged a national legislative program and wilderness preservation system out of Aldo Leopold's keen sense that we humans need to enlarge the boundaries of our ethical community, to include the land. And for Leopold 'the land' signaled the entire biota and all its interpenetrating dynamisms that support it and us. Zahnie labored to draw such a larger circle, to include wilderness and the wildness it protects. He was willing to talk to anyone for as long as it might take to help them come to see that this was, in fact, the right thing to do. As Olaus Murie once remarked, "Zahnie has unusual tenacity in lost causes." With patience that could be a winning trait.

References

Allin, Craig Willard. 1982. The Politics of Wilderness Preservation. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press.

Baldwin, Donald Nicholas. 1972. The Quiet Revolution: Grass Roots of Today's Preservation Movement. Boulder, CO: Pruett Publishing Co.

Bay, Crandall. 1983. "Zahniser, Howard Clinton (1906-1964)." Pp. 741-742 in Richard C. Davis (ed.) Encyclopedia of American Forest and Conservation History. Volume 2. New York, NY: Macmillan Publishing Company.

Codispoti, Amy. 2000. "An American Wilderness Vision." Journal of the National Wilderness Conference, 6-7.

Davis, Richard C. 1983a. "Wilderness Preservation." Pp. 693-701 in Richard C. Davis (ed.) Encyclopedia of American Forest and Conservation History. Volume 2. New York, NY: Macmillan Publishing Company.

Davis, Richard C. 1983b. "Wilderness Society." Pp. 701-702 in Richard C. Davis (ed.) Encyclopedia of American Forest and Conservation History. Volume 2. New York, NY: Macmillan Publishing Company.

Harvey, Mark W.T. 1998. "Howard Zahniser: A Legacy of Wilderness." Wild Earth, Vol. 8, #2 (Summer): 62-66.

McCloskey, Michael. 1966. "The Wilderness Act of 1964: Its Background and Meaning." Oregon Law Review, Vol. 45, #4 (June): 288-321.

Nash, Roderick. 1963. "The American Wilderness in Historical Perspective." Forest History, Vol. 6, #4 (Winter): 2-13.

Nash, Roderick. 1968. Wilderness and American Mind . New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Roth, Dennis. 1995. The Wilderness Movement and the National Forests. 2nd edition. College Station, TX: Intaglio Press.

Zahniser, Edward. 1984. "Howard Zahniser: Father of the Wilderness Act." National Parks, Vol. 58, #1/2 (Jan/Feb): 12-14.

Zahniser, Edward. 1992. Where Wilderness Preservation Began: Adirondack Writings of Howard Zahniser. Utica, NY: North Country Books.

Zahniser, Howard Clinton. 1947. "The Wilderness Society: What it is, Does, and Hopes to Accomplish." Journal of Forestry, Vol. 45, #1 (Jan): 33-35.

Zahniser, Howard Clinton. 1953. "Wilderness in a Multiple Use Forestry Program." Pp. 171-173 in Proceedings of the Fourth American Forest Congress, 1953. Washington, DC: American Forestry Association.

Zahniser, Howard Clinton. 1956. "The Need for Wilderness Areas." Land & Water, Vol. 2 (Spring): 15-19.

Zahniser, Howard Clinton. 1957. "The Wilderness Bill and Foresters: An Address by Wilderness Enthusiast...Before Washington Section SAF [Society of American Foresters]." American Forests, Vol. 63, #7 (July): 6, 51-54.

Zahniser, Howard Clinton. 1959. "The Case for Wilderness Preservation Legislation." Pp. 104-110 in Proceedings: Society of American Foresters Meeting, 1958. Washington, DC: Society of American Foresters.

Zahniser, Howard Clinton. 1963. "Wildlands, a Part of Man's Environment." Pp. 346-354 in A Place to Live, The Yearbook of Agriculture, 1963. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Agriculture.

Zahniser, Howard Clinton. 1964. "The People and Wilderness." The Living Wilderness, Vol. 86 (Spring-Summer): 39, 41-42.